1 -The worthy distinction between nonfiction and journalism

I call myself a journalist rather than a “nonfiction author” or a “science writer” for a reason. “Nonfiction” isn’t just vague, it’s ambiguous. The category of not-made-up things includes essays, memoirs, and histories, as well as books by famous politicians, pundits, TV comedians, athletes, and artists. This hodgepodge makes me grumble, because it oughtn’t include journalism. Journalism stands apart, because creating journalism entails going out into society, interviewing living people, and uncovering new material. It’s risky — because it’s real. While memoirists ponder at home, and historians poke around in climate-controlled libraries and archives, journalists endure the Earth’s conditions and navigate the complicated agendas and personalities of people. Craftily, essayists often appear to deliver fresh information, but more often than not this information is frozen, already wild-caught by a journalist. In an age when so much is endlessly rehashed and opined-upon, I reserve my respect for the discoverer — the first ascenscionist, as it were. Speculators, the way I see it, don’t even belong in the domain of truth-tellers, but in another popular category called science-fiction. “Science writer,” meanwhile, specifies a subject while leaving the method mysterious. It’s as unhelpful as “biographer.” My concern: is that biography about Isaac Newton, who died 300 years ago, or my college roommate, who’s barely 40, and probably conducted a couple of physics experiments this week?

Bluntly: did the writer, in unfamiliar terrain, pull off some balance of participating and observing, or just sit somewhere comfortable and… pontificate?

I suspect that libraries are not more careful in making this distinction because they’re overwhelmed, and that bookstores don’t bother because they see print merely as an entertainment commodity. But what I can’t fathom is how neither the New York Times — an ostensibly-journalistic enterprise — nor the Pulitzer Prize committee nor the National Book Award committee recognizes the distinction. In its annual list of 100 notable books, the Times manages to classify nonfiction books both confusingly and incompletely: by type (memoir, essay) as well as by subject (biography, science, sports, sociology, current affairs, foreign affairs.) What about history? Where would an environmental book go? And why, over the last few years, have only a quarter of these books been works of journalism? The Pulitzer Prize and National Book Award committees, meanwhile, refer only to “general nonfiction” and “nonfiction” — even though there’s nothing general about such a broad category. Over the last two decades, the first group has recognized journalists about half the time, while the figure for the second group stands at not quite a third. There’s a chance that these institutions choose to laud works about the distant past more than works about the recent past because they’re not yet sure what to make of what just happened. The dust, so to speak, hasn’t settled yet. This would be especially sad for an outfit called the Times. But there’s also a good chance that they — and us — are impaired by rosy retrospection, which makes the far away and long ago that much more fascinating than, you know, last week’s news.

In non-fiction as much as fiction, stories that transport me to new places are what I crave. In non-fiction, though, I care not just what a book is, but how it was made. Facts have fantastic power, especially fresh facts, all the more so if it took some effort to rake them in. Such facts have style. That’s the reason I make the distinction: to write my words, I interact with the world, and — especially in a down-and-out era for such professionals — I think the world of writers who do as much.

—

2 – My favorite journalism

I get book recommendations all the time. “You should read ___,” someone says. “It’s so good.” To a guy who doesn’t like adjectives much, “good” is about as useless as “nice” or “tasteful.” I happen to think drinking out of a wine bottle is nice, and that white tablecloths are not tasteful — so a lot of good those squirrelly, subjective adjectives do. As such, I assess nonfiction books — especially journalism books — based on three criteria: 1) reporting & research, 2) thinking, and 3) writing. In the first category, I want work backed up by industrious, thorough investigation — in-person and in-situ as much as in-library. This does not mean the work needs to be the size of a doorstop, but it does mean that the author examined his/her subject definitively, and was relentless in hunting down information in the service of readers. To ace the second category, a writer needs to use some imagination and put the story he/she has gathered in perspective. It must not rehash stale arguments, or cite cliched, musty examples. It should, in other words, be deep and fresh — and aware. The last category is the trickiest, because writing is an art, and for every person who loves David Foster Wallace, there’s another who can’t stand his showy syntax. I think he, and Steinbeck, and Joe Mitchell were word wizards. They wrote clear sentences. They were witty, funny. Fluid. Deliberate. Bad writing, on the other hand, can suck for so many reasons, and always registers, as one of my grad school advisors put it, as a bag of sentences. A bag of sentences does not a good book make.

Those are my three benchmarks. The way I see it, a whole mess of writers have serious talent in two of the three categories. Rare, though, are journalists who excel in all three. But they exist, and include a lot of New Yorker writers, starting with John McPhee, Richard Preston, Eric Schlosser, Robert Caro, Susan Orlean, and Jill Lepore. Their books don’t just captivate me, but wow me — and deserve a solid 5 out of 5 stars.*

By focusing on method, subject/topic becomes almost irrelevant. A few of my favorites are engineering-heavy (“Command and Control,” “American Steel,” and “The Deltoid Pumpkin Seed”**), a few are war-focused (“Dispatches,” “Hiroshima”), a few are politics-rich (“What It Takes,” “The Power Broker,” “All the President’s Men”), a few cover the peculiarities of a place (“The Meadow,” “Great Plains,” “In Limestone Country”), but most — including the books usually classified as “environmental” (“The Control of Nature,” “Cadillac Desert”) — are a rich blend, as much political and sociological as historical. These include “The Shadow of the Sun” (and everything else by Kapuscinski), “The Right Stuff” (and everything else by Tom Wolfe), “Lenin’s Tomb,” “Zeitoun,” “The Oregon Trail,” and “Random Family.”

So please, pass on your book recommendations, but don’t tell me that a book’s good, or what it’s about. Tell me how it was made, and how its components stack up.

*You can also see which fiction writers I consider masters: George Saunders, Nathan Hill, Jennifer Egan, Miranda July, Don Dellilo, and the Four Fs: Foer, Franzen, Fountain, and Ferris.

**DPS also features my single favorite McPhee sentence: “John Fitzpatrick was in Neshaminy, pumping Esso.” Say it out loud, and feel the unusual way it rolls off the tongue.

—

3 – How I report & write, including equipment and techniques

Aside from computers, the tools I use are as basic as can be.

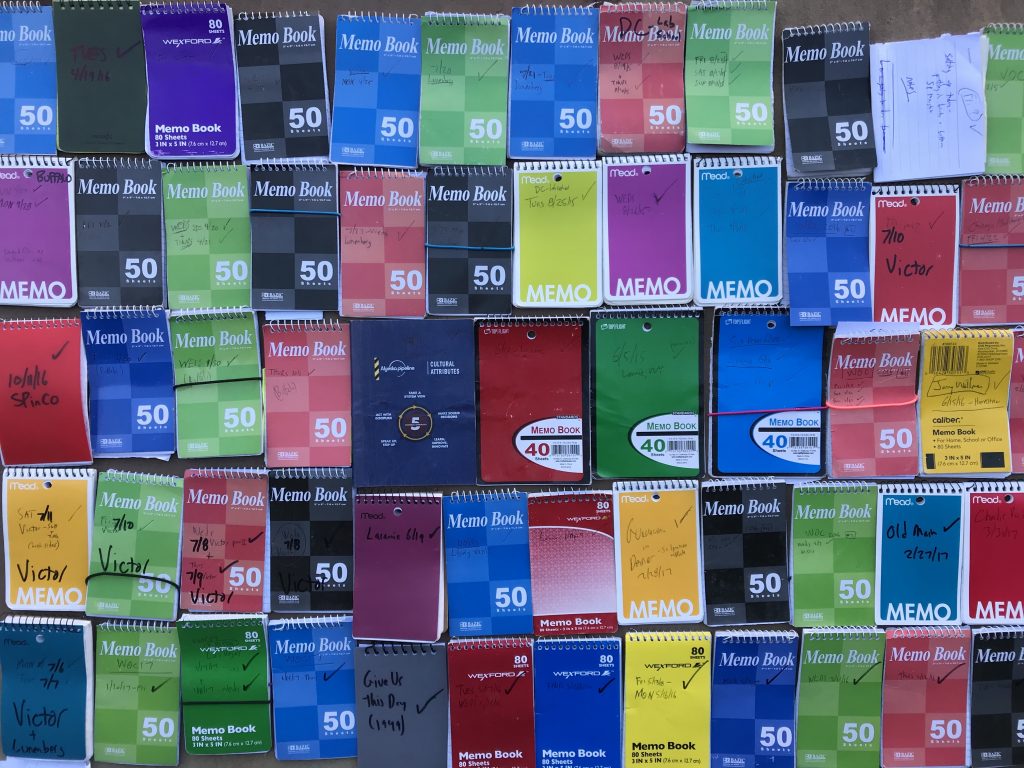

notebooks: I use the cheapest and lightest 3″ x 5″ notebooks I can find, so that I don’t get twee and self-conscious about filling them up or storing them. I like the 50-page college-ruled (aka lined) memo books that are spiral-bound on top; a couple will fit in any pocket. I buy multi-packs on Amazon, in assorted colors, at 60 cents each. (I once bought some Rite in the Rain all-weather notebooks, and treated them like expensive silver, waiting for just the right occasion to use them. The occasion never came. I find it easier just to carry a Ziploc bag.) With a sharpie, I label the cover of each notebook with the date/subject/place, and a check mark once I’ve transcribed the notebook’s contents. After that, I bundle ’em up with a rubber band, and toss ’em in a bucket for safe keeping.

writing implements: In the pen vs. pencil debate, I’m pen all the way – even though ink, ehem ehem, oxidizes. Only once, in the Arctic, did a pen fail me on account of cold. (I had a backup pencil.) Otherwise, my opinion on pencils, which has stood since my Algebra teacher allowed me alone to use a pen, is: screw pencils. I think I’d use a crayon before I’d use a pencil. I like to stash a ballpoint pen under my baseball hat, tip aiming down, to make clear to the world that note-taking is a possibility at any time. I’m ambivalent about the make or model of my pen except that the cheaper the better, which makes free hotel and hardware store pens the best.

digital recorders: I have a few of these gizmos, because beyond one-on-one interviews, I sometimes leave one with a subject for a while, or use two simultaneously (so that I can report from two places at once.) The model I have is the Olympus VN-8100, which costs 3x what it did eight years ago — but in my opinion, any small digital recorder that takes AAA batteries, has a few GB of memory, and connects via a USB port will do. These things are so small and light that I can cram one in any pocket (and keep it dry in a Ziploc.) While these devices are valuable in the extreme — providing a record of exact words used — they’re also dangerous, in that the more you record, the more you need to listen to and possibly transcribe. Even though I’m a fast transcriber, I nevertheless hate transcribing, and can only do so much of it in a day. Besides, I don’t work in audio: I’m a writer, not a podcaster. So I try to reserve these guys for special occasions or notable/touchy/rare interviews.

phone: like most reporters (or most Generation Xers?), I’d much rather interview someone over the phone than over email. Talking offers so much more wiggle room — to explore, to ramble, to dig, to listen (which is what so much reporting is all about), to enjoy a conversation. If I’m at my computer,* I’ll plug in ear buds, and transcribe the conversation as it unfolds. When I do this, my last concern is spelling. My only aim is to keep up, and often I’ll say, “can you repeat that?” Few people seem to mind. I save each conversation as a separate text file (more on that below), with a note at the top detailing the subject, date, time, and duration of the call. *If I’m NOT at my computer, I scribble frantically in a memo book (or on a menu or magazine or envelope), since I can’t write nearly as fast as I can type — and no matter what, I end up with something resembling the work of a six-year-old. And if I don’t have those earbuds with me, I do this with my phone balanced between a shoulder and an ear, an act that was a lot easier with an actual telephone than an iPhone. Back in computerland, I type up a transcription of the conversation as soon as I can.

computers: I do 95% of my writing on a big (27″) iMac, far from the voices and noises of coffee shops or shared work spaces. When traveling, I carry an itty-bitty (and now-obsolete) Macbook Air, and primarily use it to transcribe notebooks while the ink in them is still fresh. My handwriting is as bad as my memory, so this is a must. This transcribing happens almost exclusively in hotel rooms, late at night, when I’m tired from the day’s reporting – but there’s no other option. I’ve never managed to summon the energy to transcribe anything on a plane, or even in an airport, and only once have I pulled it off on a train.

software: A long time ago I figured out that when writing I want nothing to do with fonts or formatting or spell-checking or hyperlinks or other features. All I want to mess with is words (in Times New Roman 12.) So for at least a decade, the program I’ve turned to for composing has been… TextEdit. Yep, good old TextEdit, the 6MB application pre-installed on Apple computers since 1995. I wrote this post in TextEdit, and saved it — like all my documents — as an rtf file. It amounted to 16KB, which is small enough to metaphorically put in a Ziploc. I write everything in TextEdit — from single page transcriptions to 60-page chapters. Aside from typing, copying, pasting, and deleting, the only other action I perform in TextEdit is bolding sections that I find noteworthy. Apple-B, baby. (More on this below.) That’s all the futzing I do. Eventually, long after my research and reporting is wrapped up, and my drafts are nearly final, I take all the chunks I’ve written and compile them using a proper word processing application called LibreOffice. LibreOffice is a free, open-source, slightly slicker (and less crash-prone) analogue of Microsoft Word. The application is 100x the size of TextEdit, so it takes longer to load, which is one more reason I don’t use it to write the hundreds of documents that comprise a book. But by saving my use of this application until I near the finish line of book writing, I give myself a little signal that I’m making progress. Believe me when I say that, in this way, few formatting endeavors rival the experience of building a table of contents. That TOC is a thrill every time. Aside from TextEdit and LibreOffice, the only other application I use is Chrome, for online research. (A lot of folks have recommended various reference-tracking apps, like Zotero and Endnote and Mendeley, but none agrees with me.)

So with those material (and digital) things, I go about my research/reporting/writing in the following way.

I like to keep my source material, so PDF’s make me happy. So do photos of pages from books (thanks, iPhone.) I create a separate folder for every source, eventually grouping the sources in sub-folders by topic. (I’m not averse to duplicating sources, and storing them in two or three sub-folders.) Every source folder gets its own notes file, which is just the material (quotes, facts) that initially stands out. These rtf files, invariably, are little more than lists ordered by page numbers. One of my better tricks is that I err on the side of caution when I jot down notes, scraping up far more than I’ll eventually use. Once I’ve read my notes many times through, and made sense of what’s fresh/good/useful (and related to the outline I’ve devised), I go through each notes file and embolden the really good material. Then I make a new document, and copy all of my emboldened text into it. That leaves me with a 1) source folder, 2) a notes file, and 3) a selects file. I do this with all of my sources, and with my interviews, too. I treat the original transcription as a source, and embolden the quotes/explanations/facts that leap out, then transfer these to a notes file. Dozens of interviews later, once I’m able to discern usable material from superfluous material, I embolden the good parts, and transfer them to selects files. As you can imagine, this leaves me with lots of folders full of many files. But everything’s there: the original stuff (which allays any anxiety that I’ve forever lost some crucial nugget) and the culled stuff, which makes writing manageable. By culling, I make it possible for my brain to process a chapter’s contents in a single big breath (aka one morning.) That’s the key, I think. The brain (my brain, at least) can only hold onto so much information for so long. I suppose it’s like a Shop-Vac, limited not just by voltage and the diameter of the hose feeding it, but by the volume of the contraption itself.

Once the Shop-Vac that is my brain is full, I write my first draft (in TextEdit, of course.) This is a new document, called draft 1. If I’ve done a good job culling my select material (and scheming up an outline), writing is fun and painless and pretty quick. One important note here, before moving on: Do I assign myself a daily word quota? I do not, because I think preparation serves me much better than pressure. (If you’re a journalist in the 21st century, you’re under enough pressure already.) I couldn’t care less if my seat is warm. I’m a writer because I like to write, and if I’m not feeling it, it’s because I’m not ready, most likely confused. In times of confusion, I go in one of two directions: off in the woods to exercise, or over to see friends. Anyway, after so much time gathering and culling information, I’m usually antsy to get writing, and have no problem producing three thousand, four thousand, even five thousand words in a day. With a blueprint and materials on hand, the only tool I have — my mind — does not get overtaxed. At worst, I’ll leave some TKs or XXs where I need to fill in some contextual research. Since I like to start early, with an empty stomach, I can tell it’s time to stop for the day when my stomach starts rumbling, which could be anywhere between noon and 8pm. After shoving food in my face, I like to go for a long uphill bike ride to clear my head and return to planet Earth.

When I sit down the following morning, I start by employing another little trick: to alleviate my inner worry that I might do more harm than good, I duplicate yesterday’s draft, retitle it “draft 2,” and start fresh — so that, no matter what, I can always revert to “draft 1.” This freedom-to-be-creative-without-causing-harm seems crucial, and I’m always grateful that all it takes is Apple-D (duplicate). In case you don’t believe me, with the fourth chapter of RUST (“Coating the Can”), I wrote 33 very different drafts.

One final trick: halfway through the draft-writing, I show what I’ve got to whomever I’m writing about, to hear his or her take. (I don’t grant my subjects editorial powers.) When we talk, I transcribe our conversation (recording it as yet another rft file), and use this as another valuable source. Where this move once felt scary, now I find it reassuring. The way I see it, my subjects are going to read what I write, and probably find a mistake — and I’d much rather have the chance to fix something than merely find out my error has been printed ten thousand times over.

Roughly, that’s how I proceed from gathering to culling to building and refining. Each step demands a different kind of energy and works out best under unique conditions. I like to gather and cull in silence, while I like to write with music playing. (Anything from Japanese rap to Bach will do, as long as there are no word-filled lyrics to latch onto.) When gathering, I surround myself with books and magazines and photos, and leave my window-shades open. When writing, my desk is a clean slate, and the shades are closed. My final two thoughts on conditions that allow for writing: stand-up desks are not for me, and neither are shoes.